The Owner Built Home & Homestead

Ken Kern's advice on selecting a homestead site, building climatology and central heating.

By Ken Kern

January/February 1971

THE OWNER-BUILT HOMESTEAD, CHAPTER 1

SELECTING THE SITE

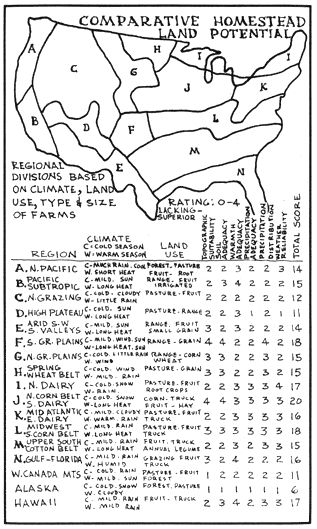

Will Rogers gave the advice: "Buy land . . . they ain't making any more of that stuff." And modern day population alarmists predict standing room only for the future. All the land will be occupied, they say, to feed and house and transport people. The population of the U.S. is estimated to be 700 million in one hundred years. Of the 2 billion acres of land in the U. S. only one-third is considered favorable to crop production. Alternative solutions appear to be (1) State socialism with overhead control of births, and (2) a strict limitation on population growth, keeping business (and private ownership and land speculation) as usual.

But there is now a Third World Front that is viewing the land and population issue in the new light of the primacy of the home. First of all, if we used only our prime cropland and cultivated it as intensively as the Japanese, and reduced bureaucratic wastage, and consumed more firsthand foodstuffs rather than processed trash and animal products, then we Americans could feed a tremendous population. (2 billion people, according to U. S. Department of Agriculture, 1958 Yearbook). The population explosion scare is overdrawn: It diverts concern from the real issue which is the comfort and beauty of people, versus (1) making money (capitalism) and (2) worship of the state (communism).

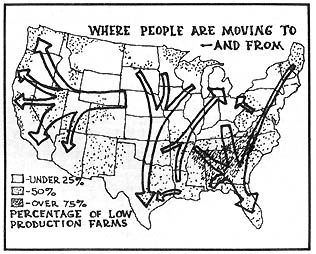

We must come to terms with this so-called land question before selecting or acquiring our homestead site. Understanding the issues will most definitely influence our choice of location. For one thing, anyone who has done any land shopping realizes that there is currently a strong demand for land. The same demand in the 1930's had its origins in unemployment and insecurity. Today's influence is more sophisticated: Industry is dispersing to the countryside . . . as is the suburban growth of population. An estimated million acres is taken up yearly by residential, industrial, highways and other nonfarm use. Farms are enlarging to make labor and machinery investments more efficient.

The amount of land now being withdrawn from the market for speculation is frightening. Traditionally, the investment in land is especially high during and immediately after a war. Land is considered a safe hedge against inflation. Speculative land is just not available . . . certainly not to the prospective one-horsepower homesteader. We must therefore outwit the carpetbagging speculators by finding attractive homesites that are not attractive to their investment dollars.

A brief study into rural appraisals indicates clearly the speculative value of various property features. Closeness to rail transport or a main road may be important to a commercial farmer but it is probably not worth the additional land cost to a small acreage homesteader.

Level ground is far more valuable to a land speculator than sloping ground. The speculator knows that level ground farming permits a more uniform type of vegetation. He knows that power equipment can be used to more advantage. But a small homesteader may find that drainage is poor on level ground, water accumulates and leaches nutrient materials down into deeper layers forming hardpan and poor aeration which becomes impervious to plant roots. A hilly site location may not be adapted to large scale farming operations but there are actually more advantages to the homesteader in choosing a hilly or mountainous location.

A level, protected valley receives much radiant energy from the surrounding slopes during the daytime, and is consequently warmer than the surrounding hillside. At the same time, wind movement in a hilly region provides better ventilation and therefore less heat build-up. At night, air drainage is accentuated in hilly regions and a process of temperature inversion takes place. Reservoirs of cold air drain from surrounding slopes to the low-lying basins.

The climatic comparisons of a valley and adjacent hilly regions was made in Ohio some years ago (Wolfe: Microclimate and Macroclimate of Neotome Valley: Ohio Biol. Survey; 1949). The hilly site consisted of a sort of grotto, weathered out of cliff-faces and located at the cove of a valley. The grotto had 276 frost-free days, while the valley frost pocket had only 124 frost-free days. Maximum-minimum temperatures for the grotto were 75 and 14; for the valley, 93 and 25.

A southern slope receives more insolation than a northern exposure. The degree of slope determines the amount of insolation received: According to the U. S. Department of Agriculture Yearbook (1913) land in southern Idaho that slopes 5 degrees to the south is in the same solar climate as level land some 300 miles south in Utah. Also, ground sloping 1 degree to the north lies in the same solar climate as level land 70 miles further north. The warmest slope is the one most nearly perpendicular to the sun's rays during the growing season. Steepness should therefore increase with latitude.

The southwest slope is warmer than the southeast slope. Sunshine on the southeast slope occurs shortly after the prolonged cooling at night. Also, evaporation of the morning dew requires energy. The west slope of a hillside has the highest average air and soil temperature and the longest frost free season. Cold injury to plants is greatest on the east slope; heat injury greatest on the west slope. Slopes facing north tend to be more moist than slopes facing south.

Temperature considerations are different for the Eastern and Western regions of the U. S. A north-south distance is important for a frost-free difference in the Eastern half; elevation determines temperature differences in the Western half. Latitude and elevation are therefore essential considerations in determining the length of the growing season. Growing season is the main limiting factor in developing a homestead in Alaska. (It is the average period between the last killing frost in Spring and the first killing frost in Fall.) The duration of extreme temperatures . . . both heat and cold, the amount of sunlight, and the amount of rainfall, are further climatic considerations that should be considered when choosing a homestead site.

Next to climatic and topographic factors, soil type is of foremost importance. Soil classification is a very involved subject and will be dealt with later (there are 1000 types of soil in California, for instance). But a few general pointers about soil should assist one in land selection. A dark soil color usually indicates high fertility. Grey and yellow indicate poor drainage and light colored soil, low fertility. Look for medium-textured soils: Extremes of both sand and clay are usually low in productivity. Sandy soils thaw first and warm up faster in the spring than do clay soils. This is due to their lower heat capacity, lower thermal conductivity and reduced amount of evaporative chilling.

Soil fertility can also be determined by observing plant growth. Fast growing weeds like giant horseweed or cockleburr indicate good soil conditions; red sorrel grows in poor acid soil. If the plant has a deep color the soil in which it grows is probably fertile. Tree limbs that extend upward and do not droop also indicate fertile soil. Walnut, cypress, whiteoak and cottonwood trees are all good soil indicators; blackjack and pine grow in poor soil.

It may be profitable for evaluation purposes to list all the considerations-in order of importance-that go into choosing a homestead site. There are indeed many, and no one site could possibly be favorable in all respects. So we therefore learn how to adapt and how to compensate for shortcomings. If the latitude falls short of expectations, compensate by increasing elevation. Or one can pick a site that has a proper orientation and slope angle so that the angle of exposure to solar radiation compensates a high latitude that receives little radiation. A low annual rainfall can be supplemented by dew and fog, or by irrigation and water storage. Soil texture may be substituted for moisture: Asparagus thrives in sandy soils in areas where heavy soils would be much too wet for it.

When selecting a homestead site, start with a general evaluation of the region, state, county and community down to specific study of the actual site. The most important tool for this research is maps. They tell all. Start with a set of U. S. Geological Survey maps. They are accurate, show topographic features and cover about one-half of the U. S. The Soil Conservation Service can supply you with aerial photographs for most regions of the U. S. Soil maps are also available from this agency. The U. S. Bureau of Public Roads and the U. S. Post Office Department have informative county highway maps and maps showing rural mail routes.

More specific site information is available on County record. The local Title Company oftentimes has more up-to-date land title information than County offices. But from County Plat Books record information can be found regarding assessed valuation, amount of taxes paid, special assessments for drainage etc., and dates and prices on sales of adjacent properties. Individual property owners names are indicated on County Plat Books; addresses can be found in the Assessor's Office.

On some remote properties it may be necessary to find site information from Government Township Plats. These are available from the U. S. General Land Office or filed with the State Auditor. Individual counties may also have Government Township Plats on file-check with the County Surveyor.

Map study is one of the finer joys that go with locating a homestead site. Maps have a continual fascination: Nothing short of earth-contact can give one as much understanding and appreciation of the land. A roll of maps (folding maps is like cutting bread: Maps should be rolled and bread, broken) is the one best tool for site exploration.

Once a person narrows his land search to a specific county or community, he should move there and begin his quest for the actual site. For starters, inspect the tax rolls in the County Treasurer's office for properties on which taxes have remained unpaid for a number of years. Distressed or unwanted property can often be bought for unpaid taxes. Banks and trust companies are also engaged in liquidating property at bargain prices. Auctions are another good source, or one can advertise for property in the local newspaper. It is a good practice to get acquainted in the community: Ask around for available land and let it be known you are in the market. As a final, rather desperate resort, roll up your map and visit the friendly Real Estate Broker.

Something should be added to this subject of unwanted or distressed property. People-even professional land speculators-are unimaginative when it comes to developing "problem" sites. Their heads are too much into the money earning or commercial aspects and not into terracing, planting, excavating, filling, or the thousand other possibilities for adapting the land to fit one's needs. Also, homestead site requirements are flexible and adaptable-not specific as is the case with a housing development.or a commercial farming enterprise. So it is good advice to capitalize on the fact that one can profitably utilize a piece of land that nobody else wants.

After the homestead site is located, start the land transfer proceedings by first making an appraisal map. This map is drawn mostly from on-the-ground site inspection. It should show an outline of the property according to the complete legal description. Important topographic and natural physical features should be shown (such as streams, fields, wood lot, etc.) Any improvements such as buildings, fences or roads should also be indicated. A tentative homestead layout and land-use sketch can also be suggested on this map.

At this point it would be prudent to confer with any county officials who may be involved in passing approval on the land transfer transaction. First check with the Planning Office for possible zoning restrictions. Find out too about building restrictions. The County Health Department may have something to say about sanitation requirements. At the County Recorders office you can determine if the property can be legally transferred. Most states have land-division regulations and many counties require a legal land survey before property can be sold.

At this stage in the land transfer transaction you probably know your way around the county offices: County clerks likely know you by your first name. You, therefore, may as well do the title search on your prospective land. Title insurance companies customarily perform this service-for a generous fee. They issue a mortgage policy that protects only the value of the land. If you build a $20,000 homestead on an insured $1000 site, and a missing heir later arrives to claim the property and cloud the title, you recover only the $1000 from the title insurance.

The whole operation is costly and ridiculous because with very little effort you can determine yourself the legitimacy of your land title. Merely check the Tract Index in the Recorder's office. Some counties keep an Abstract of Title on record. This is a condensed history of all recorded transactions for the parcel of land that you are buying. By examining the abstract, drawing up a simple deed, and preparing a closing (payment) statement, you keep several hundred dollars from reaching the sweaty palms of Title Officer, Escrow Agent and Real Estate Lawyer.

The simplest method of land transfer is to have the seller supply credit to the buyer (if the transaction is not a clean, cash deal). Either a deed is given to the buyer with the seller taking back a mortgage, or the sale is made under an installment purchase contract. In this latter case the legal title remains with the seller until all or a specified portion of the purchase price has been paid. The Contract of Sale is preferred over the mortgage contract. In cases of default, the mortgage contract requires an expensive foreclosure sale; a contract of sale is merely terminated.

Most stationary stores carry Deed of Conveyance forms. After the deed is made out have it signed before a Notary Public and recorded in the County Recorder's office. Then when you move onto the land, file a Homestead Exemption. Most state legislatures have adopted this statute to protect the value of the family home from creditor claim.

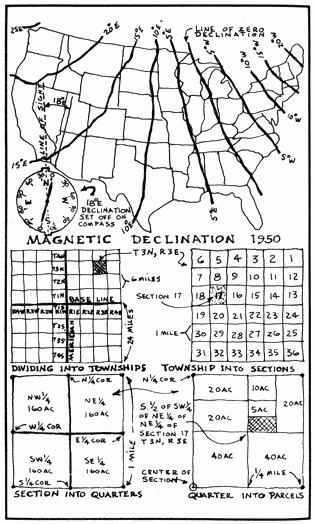

At some point in the land transfer procedure you will want to check out or establish property corners. Again, with a little knowledge on the subject, you can dispense with the services of yet another greedy professional. Land surveying was my occupation for 5 years, so I'm especially aware of how expendable the operation actually is.

The 13 original colonies used a metes and bounds survey-the most simple to retrace, as it starts from a known point and goes a set distance and set bearing. to the next point. In 1785 the government adopted the rectangular survey. This type applies to 29 states. In this land division a North-South meridian line and an East-West base line is first established. At the intersection of meridian and base an area is divided into 24 mile squares (called townships). Each township is divided into 36 squares (called sections). Section corners and half-section corners were originally set by the Government Land Office. The original survey notes for setting these corners are available to the public from the General Land Office. Missing corners can often be found or re-set by retracing the original notes. Land parcels can be surveyed out of sections by starting from known section corners and following the bearings and distances established in the original survey.

The only tools needed for this "homesteader survey" is a 100-foot steel tape and a pocket compass. The compass should be the type that rotates with respect to the box in which it is mounted. The circle can therefore be turned through an angle equal to the magnetic declination. The observed bearing will then be true and not magnetic. East of the line of zero declination (see drawing above) the North end of the compass points West of North; West of that line it points East of North.

Selecting a site which best satisfies one's homestead needs should be done with care. Many factors should be considered. This chapter falls short in mentioning all the necessary considerations or the way they may vary with individual needs and circumstances. But the following check list does provide a start in evaluating those items considered most important for making a wise selection.

CHECK LIST FOR SELECTING A HOMESTEAD SITE (in order of importance to the author)

1. Adequate domestic water supply

2. Proper solar exposure

3. Sufficient space

4. Adequate growing season

5. Air purity

6. Reasonable land costs and taxes

7. Favorable natural topography

8. Local employment opportunities

9. Good soil conditions

10. Availability of natural resources

11. Adequate precipitation and drainage

12. Neighbors and neighborhood nuisances

13. Zoning and building regulations

14. General cost of living

15. Natural beauty of area

16. Local and state political status

17. Electric power supply

18. Transportation and road access

19. Local medical facilities

20. Cultural and educational opportunities

21. Recreational facilities

THE OWNER-BUILT HOME, BOOK ONE, CHAPTER 3

BUILDING CLIMATOLOGY

A few years ago Professor Harold Clark of Columbia University completed an environment study which included visits to over 40 countries. Upon his return he told university students that he found hardly one instance of a private dwelling designed to suit its environmental climate. He deplored the fact that practically all modern dwellings throughout the world are patterned after the box-like European houses which fit the cold European climate. If Professor Clark could have conducted his environment study a few centuries ago, however, I am sure that his concluding observations would have been more favorable. For the indigenous and often primitive architectural forms of that time had become adjusted to local climate through a long process of trial and error.

Architecture these days ignores environment. Witness the growth of the world's cities, which violate natural principles of summer cooling. Contrast the cool, shady meadow found in nature with the exposed acres of urban pavement, concrete buildings, and reflecting roof-tops. Compatibility of the building to its environment is currently neglected as modern designers devote a disproportionate amount of attention to appearance and fashion-which, of course, boost the sale value of the package.

Owing to the extensive use made of climatic averages in describing regional climate conditions, there is a widespread tendency to regard climate as uniform in respect to each latitude and each season. In dealing with actual climate, however, and especially in relation to building design, nothing could be farther from the truth. The old health-food adage, "a carrot is not a carrot" (comparatively, in food-value content), holds true in the meteorological field as well. That is, "temperature is not temperature"; human reactions to temperature depend upon the ability of the body to lose heat to the surroundings by convection to the air, by radiation to the surrounding surfaces and by evaporation of moisture from the skin. Body reactions therefore depend not only on the temperature of the air but also on its humidity and rate of movement as well as the mean (or average) radiant temperature of the surrounding surfaces. It is utter nonsense to talk of a "72° F. Design Temperature." A dry bulb of 72° F. temperature at 90% relative humidity with a 10-foot-per-minute air movement will convey the same effective temperature as a 100 ° F. bulb at a 10% humidity and a 100-foot-per-minute air movement. In both instances the combination of meteorological factors will produce an effective temperature of 80° F. in a room where the walls, floor, and ceiling are at the same temperature as the air. When the surrounding surfaces are not at air temperature, an altogether different temperature index is employed to measure the actual meteorological conditions. This "adjusted" index is called the Corrected Effective Temperature (C.E.T.).

The three basic climate relationships should accordingly be kept in mind. This will prove most helpful in cooling or heating the owner-designed, owner-built home. Here they are:

1) Temperature is related to effective humidity. As temperature rises, relative humidity drops. When high temperatures combine with high humidity, the body has difficulty in perspiring and acute discomfort is experienced.

2) Air temperature is related to average radiant (or surface) temperature. In order to keep the body in an optimum-comfort zone under low air temperature conditions, the radiant temperature must be kept high. And in summer, when the air temperature is high, a low radiant temperature is required.

3) Air movement is related to both temperature and humidity. Up to a certain point, high temperatures can be counteracted by air movement.

After discovering a way to incorporate the foregoing climatological principles into a single index, the American Society of Heating and Ventilating Engineers produced the Effective Temperature Scale.* Even the effective temperature scale has its limitations in terms of actual body comfort. For instance, cold concrete floors in a room of otherwise comfortable effective temperature will produce discomfort due to vasoconstriction of the feet. If the feet lose heat rapidly from contact with a cold floor, a person will experience discomfort even though the "official" effective temperature is within the "comfort" zone. Conversely, it is possible to feel warm in a relatively cool room if seated with feet out-stretched in front of an open fire. A high ceiling temperature, also in a "comfortable" effective temperature range, will produce uncomfortable effects. And it makes a difference to body cooling whether the wind movement is directed onto back or onto the face-the latter having much more influence on body comfort or discomfort.

While designers and home builders continue their relentless defacement of the landscape over the world-from the Middletown, U.S.A., Tract Development to "Housing for the Urban Bantu" in South Africa-the research student can locate only a score of counteracting influences in laboratories throughout the world. But from these few agencies we can surely hope to achieve design-data for our comfortably situated, low cost, ownerbuilt dwelling:

o At the Hot Climate Physiological Research Unit at Oshodi in Nigeria, Dr. Ladell is conducting valuable research on shading effects.

o At the graduate school of architecture, Columbia University, a research group was organized in 1951 to study the influence of climate on the Macroform (general planning area) and Microform (architectural details). To date they have made significant progess in the study of solar control and natural air conditioning.

o In Stockholm, at the Swedish Institute of Technology, Gunnar Pleijel has published extremely interesting material on the use of the "cold sink" as cooling. Cold spots in the north sky have been scientifically determined and temperatures accurately measured. The reflection of the north sky against a wall has an effective sky temperature of 75° F.-which is 45° lower than the average of about 120° for the south sky. The mirror-like reflection of the north sky explains why livestock will stand in the shade of high-walled buildings in preference to conventional overhead shades. Professor Pleijel's more recent work involves studies in natural lighting and window protection. Protection, that is, from heat losses from inside the building or from unwanted heat gain from outside.

o Architect Jacques Couelle, director of the Centre de Recherches des Structures Naturelles, in Paris, has built a number of low cost, naturally air conditioned houses in Morocco. Ground-tempered air is channeled through an inside air space and released at the opposite end of the house.

o Dr. Ernst Schmidt, professor of thermodynamics at the University of Brunswick, has given considerable study to night-air cooling. His work has special value for use in desert locations where electric current is not available for refrigeration.

o At Forman Christian College, Labore (now in Pakistan), Professor W. C. Thoburn built several experimental cottages which use a subterranean temperature. In one building, outside air is drawn into the windows of the cellar and then down an air-well to a 14-foot-deep underground tunnel which makes a rectangular circuit of 120 feet of running length. Air is pulled up through a central duct by means of a low power fan and distributed into each room above. This system of "lithosphere building" proved to be especially efficient for summer cooling, as the earth temperature at 15 feet below the ground tends to remain constant throughout the year (76° F. at Lahore).

o Wendell Thomas experimented with a simplified version of lithospheric building in two different houses in Celo Community, near Celo, N.C. In one the basement, and in the other the crawl space provided the ground-tempering contact as well as the duct system. Cold air from the exterior house walls circulates into the basement or crawl space through slots between walls and floor. The air is warmed by contact with the lower level and then permitted to rise through a grill located in the center of the house. Both houses, in addition, have solar heating; and the crawl space house is protected from heat and cold by earth banks. In this house the temperature (without overnight-artificial heat) seldom falls, on cold winter mornings, below 60° F.

o Near El Rito, N.M., Peter van Dresser has spent much time and energy developing a low cost solar heating installation. His own solar house engages a complete heat collecting and heat storage system, but in more recent work he is perfecting a partial "sun-tempered" arrangement.

Throughout the humid, the arid, and the temperate regions of the world, these, and many more, independent investigators are making their efforts known to all who will but take the trouble to search them out. Though most of their research is still in its experimental stages, enough can be learned by the individual home builder to be of great assistance in planning a more economical and comfortable home.

In effect, this new science of Building Climatology is directed toward the control of climate. The term "Climate Control" is often seen in the literature on this subject. This control is manipulated in two ways; through constructional means and with artificial aids. Cooling by evaporation of water or by fans, and warming by heaters and fireplaces are "artificial" features which are a part of the building, and items of basic equipment which do not call for the consumption of fuel or power, are considered "constructional." (Both methods of control will be discussed in the next two chapters-Cooling and Heating.) From a practical, economic, or esthetic point of view, I feel that it makes much more sense to develop constructional features for warming or cooling the owner-built home.

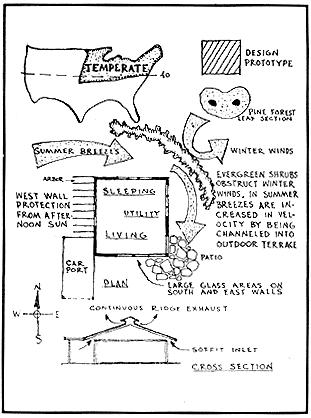

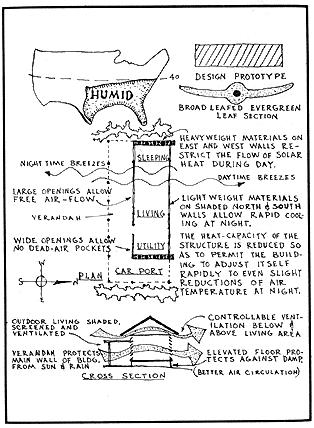

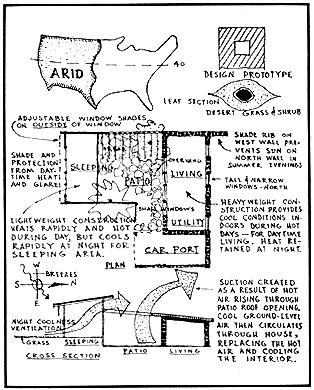

As a general summary of basic constructional considerations, I have presented in this chapter a model plan for each of the three climatic regions in the United States.

*A similar temperature index, called Sol-Air, has more recently been used by air conditioning engineers. Sol-Air temperature depends upon the solar orientation of the surface, its absorptivity to solar radiation (and to low temperature radiation), the intensity of solar radiation (and low temperature radiation), as well as air temperatures and the surface.

BIBLIOGRAPHY (books listed in order of importance)

House Beautiful; Climate Control Project, Bulletin Institute of Architects, March, 1950

Physiological Objectives in Hot Weather Housing; Douglas Lee, Housing and Home Finance Agency

Weather and the Building Industry; Building Research Advisory Board, Conference Report No. 1, Washington, D.C., 1950

Application of Climatic Data to House Design; Housing and Home Finance Agency, Washington, D.C., 1954

Symposium on Design for Tropical Living; South African Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Durban, 1957

Climate and Architecture; J. E. Aronin

The Weather Conditioned House; G. Conklin

Climate and House Design; J. W. Drysdale, Commonwealth Experiment Building Station, Australia, 1945-48

THE OWNER-BUILT HOME, BOOK ONE, CHAPTER 7

CENTRAL HEATING

"How are you going to heat it?" This is the question most often asked at the first stages of owner-builder planning. Pertinently so, as the type of heating has a major effect on room location and window placement, as well as general house design and orientation layout. To answer this question most people have no more information than the half-truths offered by heating appliance salesmen, heating contractors and fuel distributors.

The heating problem is not simple. Consider operation with just one type of fuel-consuming appliance, the oil burner. When a "high-pressure" oil burning unit is used (such as that produced by the Carlin Company), about one gallon of oil per hour is consumed. But the Williams' Oil-O-Matic model, a "low pressure" type, requires just half this amount per hour. And now the Iron Fireman Company comes up with a "Vertical Rotary" burner which requires even less, or about one-third gallon per hour.

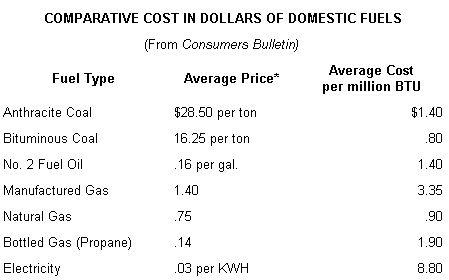

Electric power companies advertise the advantages of the "all-electric house"-the freedom from handling fuel and ashes, and the extreme simplicity and flexibility of operation. But with electrical rates at 3 cents per kilowatt-hour, heating costs will be about six times as much as with fuel oil at 16 cents a gallon. Where natural gas is available the cost differential is even greater. I do not mean to rule out the use of electricity for domestic heating. In regions where electrical rates are low, or where there are very mild winters, or in cases where an intermittent, quick-return type of heat is desired, electricity may offer inducements in cost and performance.

*As there is a wide price variation from city to city, actual local prices should be substituted for reliable comparison.

The factor of climate, of course, is of importance in heating. But air temperature is only one of several important climatic measurements. Relative humidity, solar radiation, and air movement should be taken into account. For instance, it has been found that a wind of only 15 miles per hour may increase the heat loss from a window surface by 47% and from a concrete wall by 34%. So heating plans have a close relation to windbreaks and wind baffles.

CLIMATE AND HOUSE HEATERS 2000 degree-days*-intermittent types of heat; stoves, portable heaters using gas or electricity; central heat likely to be troublesome. 4000 degree-days-space heaters popular; baseboard radiation very satisfactory; electricity and bottled gas often used; heating limited to living room. 6000 degree-days-central heating desirable, though often replaced by space stoves; hot-water heating systems popular; electric heat impractical.8000 degree-days-heat required in every room preferably central system; periphery usually sufficient to permit use of steel baseboard radiation. 10000 degree-days-central heat required in every room; periphery of house likely not long enough to permit adequate heating by baseboard radiation; electrical heating prohibitive in cost.

*The heating engineers' "degree-day" is based on difference between outside temperature and 65° F., counting by hours.

Heat is transferred in three ways; by conductors (e.g., the warm floor), by warm air, and by radiant panels. Rather than attempt to solve the heating problem through one type of heater alone, you might combine the best features of each, including the radiative and conductive effects of the heat-circulating fireplace, as well as the radiative effects of solar heat. Hot-air convection heating, which is quick-acting, can compensate for the time-lag typical of hot-water panel heating.

The ancient Romans, and later Count Rumford and Ben Franklin, and now heating engineers and physiologists have speculated on the heating process in relation to health and fuel economy. From all available evidence, I am reasonably directed toward using radiative means of heating rather than convected, warm-air types. It is important to realize that the purpose of heating a building is not to put heat into the occupant, but to keep him from losing heat. We are comfortable when we give off heat effortlessly at the same rate that we produce it. The only purpose of a heat-system is to aid the body's mechanism in maintaining balance between its rate of heat loss and its rate of heat generation.

In the case of convected heat, the air-temperature in a room must reach 68 to 70 degrees F. for basic comfort; yet this temperature unfortunately is too high for us to emit heat rapidly enough. Our pores tend to "open" (through certain nervous and endocrine reactions) and more blood flows to the surface of the body, so that it can radiate more heat to the outside air. The result is a feeling akin to exhaustion as on a hot, humid day.

Comfort at lower air temperatures can be achieved by using radiative heating methods-thereby promoting the generation of heat within the body, and the exhilaration that goes with brisk activity. In a conventionally heated room, hot air rises from the convector (usually located beneath a window) and then sweeps across the ceiling and falls down the opposite wall. Temperatures at the ceiling level are highest where they actually do the least good, comfort-wise. A temperature of 100 degrees at the ceiling may produce only a 70 degree temperature at the living zone! A smaller range of air temperature from floor to ceiling is possible by using radiant panel heating methods. Where a 70 degree air temperature is required in convected heating, less than 65 degrees is required using radiative means, resulting in a 30% saving in fuel consumption.

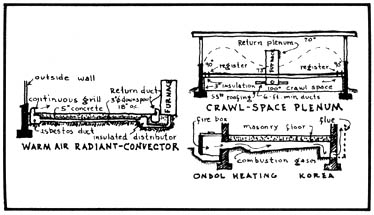

The sun or an open fire emits radiant heat rays. The Romans, by circulating hot gases from charcoal fires through ducts to warm walls and floors, created radiant heat 2000 years ago in England. The traditional Korean "ondol" heating adapts the radiant principle; combustion gases from the kitchen stove flow through a labyrinth of chambers under the floor-slab to a chimney at the far end of the room. Radiant heat then comes from the floor. Frank Lloyd Wright revived radiant heating in the Western world in developing the "gravity heat" system. He used it (1937) in the Johnson Wax Building.

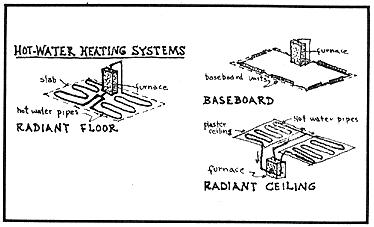

About 90% of currently installed radiant panels use hot water as a circulating medium, but a hot air radiant system is definitely less expensive to install and operate. Most water systems use steel or copper pipes buried an inch or two beneath the top surface of the concrete floor slab. This is no doubt less costly than ceiling or wall installations, but the hot-water radiant ceiling has many points in its favor. In order to achieve maximum efficiency, the water temperature in a radiant floor slab must be maintained at from 80 to 90 degrees. Yet a floor temperature of over 70 degrees will cause a rise in foot temperature and consequently an undesirable disturbance of normal heat emission from various areas of the body, since the temperature of the lower extremities is normally several degrees lower than that of the trunk and upper areas.

The fact that the floor is warm in a ceiling-heated room may at first seem contradictory. But if the entire surface of the ceiling is heated, there is no chance for convected air circulation. This makes for a uniform temperature, with radiant energy transmitted downward and intercepted by the floor surface. Water temperature in ceiling-heated surfaces must be kept at from 125 to 135 degrees.

There is a long time-lag in radiant floor heating; slow morning heating and slow evening cooling. A sudden change in weather cannot be compensated for soon enough. This is the usual objection to a hot water radiant system. However, a thinner floor slab will hasten the response to temperature change. Dividing water circuits into separate sections-one circuit for the living area, one for the sleeping area, etc.-will also cut down on heating lag. Likewise, a grid system of pipe layout is more efficient than a sinuous pattern.

The hot water radiant ceiling will of course cut down considerably on heat lag. The latest ceiling panel development-that of attaching the heat coils to the top of perforated metal snap-on panels (with acoustic "thermal blanket" insulation)-has proven to be far more efficient in heat response than the conventional plaster-lath installation. Metal is an excellent heat conductor, and becomes heated almost to the same temperature as the water in the pipes. The exposed metal should be of a matte or "flat" surface (aluminum is best); if polished it has no radiating qualities.

Another recent development in "hydronics" (that is, water heating) has come out of experimental work at the University of Illinois. Considerable time and installation expense can be saved by using 1/4 inch to 3/8 inch flexible copper tubing in place of the usual 3/4 inch steel or copper pipe, since the number of fittings can be reduced one-half. The small appliance-sized, automatically-fed boiler has recently appeared on the market. High temperature water heating combined with water heating for domestic use can be supplied at relatively low cost. Levitt has used both the 3/8 inch copper tubing and the combination water heating appliance (York-Shipley, 94,000 BTU/hr.)

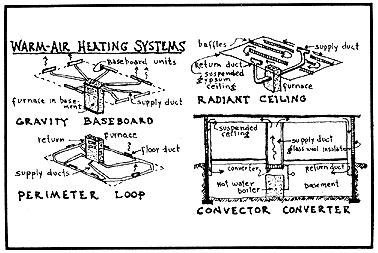

A hydronic system known as "baseboard radiation" is another current development. Heat is provided by baseboard radiation units located usually on cold walls. Some convection effects probably occur, but the units are mainly radiant in their action. Forced hot-water baseboard radiation is low in first cost and simple to install.

About fifty years ago the cast iron stove was moved into the basement and became a furnace. As a "gravity" convection heater it sent up hot air (and other gases!) through a grill in the floor. Basically this gravity warm-air heating system has not been improved upon. It is still the cheapest heating system for the small, compact home, and is perhaps found in existing homes more often than any other type. Air enters the system through one or more "cold air" or "return air" registers, and is heated as it passes through the large return duct.

About twenty-five years ago someone had the bright idea of installing a fan in the bottom of the heater. The resulting "forced-air" system allowed for smaller ducts and more freedom in design. Moreover, it was possible to keep the house and furnace on the same level. The majority of new homes are equipped with warm-air perimeter-duct or baseboard heaters-this in spite of the fact that extensive research proves convected-air heating is generally unhealthful-for heating appliance manufacturers and installation contractors are about 10 years behind research developments in their field.

Since the best method of domestic heating may be a wise combina tion of radiative and convective systems, I mention two more promising "combination" systems. From a centrally located furnace, hot air is blown down into radiating feeder ducts imbedded in the concrete slab. Hot air circulating through these feeder ducts heats the floor surface to a temperature of about 73° F. as it passes through to a larger perimeter duct and then into the room. Thereupon a blanket of warm air passes up the exterior wall where it is most needed. Since the floor surface is heated, no cold air floor register is necessary. The absence of cold air at the floor level also contributes to the "living zone" comfort.

Crawl space perimeter heating is another recently developed "combination" system. It is said to produce the most uniform temperature with the quickest response at the lowest cost. In this system the total crawl space serves as the plenum. The central down-flow furnace supplies warm air to a short, stubbed-out duct system, pointing to the far corners of the house. Registers are located around the outside perimeter of the rooms. Return air is collected in an interior wall and returned to the furnace through a short duct. When a layer of heated air exists below the floor joists, not only is the floor surface temperature increased, but also the "living zone" temperatures are made more uniform from floor to breath level.

No matter what type of heating system one chooses, if the house is not adequately insulated and weatherstripped, heating costs will be excessive. In cold climates it will cost only half as much to heat a well insulated building as a poorly insulated one. The Housing and Home Finance Agency (Release No. 126, Oct., 1949) reports that the annual fuel saving from moderate insulation of a typical dwelling in Washington, D.C. will amortize the additional cost-expense in two years! In one carefully planned experiment it was shown that coating the walls and ceiling of an experimental room with aluminum paper reduced the heating load by 21%.

It has also been found that 80% of the hourly heat loss from a concrete slab or crawl space house is through the perimeter and floor, with only 20% through the ceiling. And of this total heat loss, most occurs along the perimeter rather than downward through the floor. In two houses in Champaign, III., the one not weather-proofed required 3,000 gallons of oil in one year, whereas the same-sized house with storm sash and doors, weatherstripping of outside doors, and insulation of ceiling and sidewalk took only 800 gallons.

An efficient heating system in a well-insulated dwelling is comforting to body and mind.

BIBLIOGRAPHY (books listed in order of importance)

Radiant Heating: Pratt Institute, School of Architecture, Bulletin No. 1

Physiology of Heat Regulation: L. H. Newburg

Heating Ventilating, Air Conditioning Guide: published by the American Society of Heating and Ventilating Engineers

Fuels and Burners: Small Homes Council Bulletin No. 64

Radiant Heating: Adlam

Heating and Fuels: Consumer Bulletin Annual; Sept. 1958

Hot Water Heating: F. E. Glesecke

Chase Radiant Heating Manual: published by Chase Brass and Copper Co.. Waterbury 9, Conn.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|