The Owner Built Home & Homestead

November/December 1970

INTRODUCTION

I am intending this to be a how-to-think-it as well as a how-to-do-it book. As a designer-builder of contemporary homes-a self-appointed specialist in the low-cost field-I have long had the compulsion to express my feelings and thoughts in regard to the home-building industry, and to do something constructive for the people who are now suffering under it. I have yet to find one critic who comprehends entirely why our houses are so poorly constructed, why they look so abominable, why they cost so much for building and upkeep, and why they are so uncomfortable. Some critics blame the building contractors personally; others feel that the fault lies with urban codes and building restrictions. Some believe that expensive housing is due to the high interest rates charged by the bankers; others blame the trade unions for hampering efficient construction. Every writer on the subject seems to fondle some pet corrective measure. And every year some noted architect develops a sure-fire technical solution to the housing problem. Even more often the building material manufacturers come up with a new wonder; an improved wallboard or window or what-not which can be installed with a ten-minute saving in labor!

Everyone in the building industry appears to be busily engaged making "improvements" in his personal area of concern. But quality makes a steady decline. The end product is as inadequate and unsatisfactory and costly a house as ever. The architect spends more and more time at his drafting board, exhausting possibilities of new construction techniques and more economical arrangements; the contractor conscripts even more and specialized equipment for building efficiency; the banker resorts to undreamt-of-schemes to make it possible for everyone to buy his new home-even if he lacks money to make the down payment; building material manufacturers work overtime in their laboratories making "more and better things for better living." With all this hustle one might well expect some major improvements in new home construction. Whatever improvements occur are insignificant in comparison to the improvements that should be made. The causes of the world's housing problem still remain.

Tracing these causes to their sources has helped me to view the problem in perspective-comprehensively. This procedure has also suggested some workable alternatives as solutions to personal housing needs. Here they are in the form of seven axioms for the Owner-Built Home.

1. BUILD ACCORDING TO YOUR OWN BEST JUDGMENT. At the apex of the poor building hierarchy-and perhaps the greatest single impediment to good housing-is convention. Building convention takes two forms; first, there is convention which is socially instilled (commonly called style ), which can be altered through education. The second type is more vicious, and politically enforced. Building codes, zoning restrictions, and ordinances all fall into this clas s. In urban jurisdictions, politically controlled convention calls the shots for practically every segment of the building industry. Ordinance approval or disapproval makes the difference between having a house or having none at all. Or it may make a difference of $1,000 (average)-wasted because of stupid, antiquated building laws.

So if we are to be at liberty to build our own home at less cost, we must necessarily be free from all building code jurisdiction. This means we must locate outside of urban control-in the country or small township districts.

2. IN BUILDING YOUR HOME, PAY AS YOU GO. A building loan is another type of legalized robbery, added to that of the building codes. More than any other agency, banks have been successful in reducing would-be-democratic man to a state of perpetual serfdom. The bankers have supported and helped to determine social and political convention, and have amassed phenomenal fortunes through unearned increment. As "friends" of the home-owner they have made it possible for him to take immediate possession of his new home-and pay for it monthly for 20 to 30 years. Most people who fall into this trap fail to realize that the accumulating interest on their 30-year mortgage comes to more than double the market value of their home! If one expects any success at all in keeping the costs of his new home down to a reasonable price, he must keep entirely free from interest rates.

3. ASSUME RESPONSIBILITY FOR YOUR BUILDING CONSTRUCTION. The general contractor has become such a key functionary in practically every building operation that one soon loses sight of the fact that he is a relative newcomer to the housing scene. Not many years ago the contractor's job was performed by a supervising carpenter-a so-called master builder who had control of the whole project. Once people realize how little is involved in implementing a set of house plans, they will better appreciate the fact that the contractor is the most expendable element on any job.

Excessive profits are made by the general contractor for coordinating the work stages and assuming the responsibility for a satisfactory completion at a specified cost. For this service he receives 10% of the total cost of your house. Besides, he receives an even greater percentage on all materials which go into the structure. The contractor is an expensive and non-essential luxury for the low-income home builder.

4. USE NATIVE MATERIALS WHENEVER POSSIBLE. Much of an architect's time is spent in keeping abreast of the new "improved" building materials which manufacturers make each month. Many of the products are really worthwhile; but more often than not they are entirely beyond the reach of the average home builder. Basic materials, like common cement and structural 2 x 4's, have not appreciably advanced in price over the past dozen years. But some of the newer surfacing materials and interior fixtures have sky-rocketed in price during this same period.

By not using these high-cost materials, one of course nips the problem in the bud. Instead, emphasis should be placed on readily available natural resources-materials that come directly from the site or from a convenient hauling distance. Rock and earth and concrete and timber and all such materials have excellent structural and heat regulating qualities when properly used.

5. SUPPLY YOUR OWN LABOR. Building Trades Unions have received-and not unjustly so-a notorious reputation as wasters of speed and efficiency in building work. We all know that painters are restricted to the 4-inch brush and that carpenters are limited to the 14-oz. hammer (upon threat of penalty from union officials). Apparently more width and weight might conceivably speed up a project to the point where some union man would prove expendable.

The disinterest that the average journeyman has in his work, despite his high union pay rate, is appalling. The lack of joy-in-work or acceptance of responsibility among average workmen can be accounted for partly by the de-humanizing effect of the whole wage system. So long as the "master-and-slave" type of employer-employee relationship continues to exist in our society, one can expect only the worst performance from his hired "help". So until the dawn of the New Era approaches, one would do well from an economic, as well as from a self-satisfying standpoint, to supply his own labor for his own home insofar as he can.

6. DESIGN AND PLAN YOUR OWN HOME. Another ten-percenter with whom we can well afford to dispense in building a low-cost home is the architect-designer-craftsman-supervisor. Experience in this branch of home building has led me to the conclusion that anyone can and everyone should design his own home. There is only one possible drawback here; the owner-builder must know what he wants in a home and must be familiar with the building site and regional climatic conditions. Without close acquaintance with the site and a clear understanding of family living needs, the project is doomed to failure no matter who designs the house. An architect-even a good architect-cannot interpret a client's building needs better than the client himself. Anyway, most contemporary architects design houses for themselves, not their clients. They work at satisfying some esthetic whim, and fail really to understand the character of the site and the personal requirements of the client.

7. USE MINIMUM BUT QUALITY GRADE HAND TOOLS. If the house design is kept simple, and the work program well organized, an expensive outlay in specialized construction equipment can be saved. The building industry has been mechanized to absurd dimensions. And even with more and better power tools, labor costs rise. Or at times where labor savings occur, the difference is taken up in the depreciation and maintenance of the equipment which saved the time in the first place. Whatever way you look at it, a certain amount of work must go into building a home. If a prospective home owner is unprepared to accept the challenge of building his own home-and falls into the power tool trap-then he must be prepared to spend greater sums for a product which could very well prove inferior.

Now that I have presented the ideal program for the owner-built home, I should retrace my steps and face the sheer realities of the situation. Obviously, not all people can locate their home site out of building code jurisdiction. Nor can many people expect to finance their home from their weekly pay check. Very few people have the native ability to design an inexpensive and attractive home-one that truly fits their needs and site conditions. Even more rare is the person who can carry through all phases of building construction, or who even has the necessary free time to devote to a house building effort. And how many people do you know who could take the raw material resources and process them into building materials for wall, roof, and floor? One has only to observe current owner-built home flops to appreciate the fact that we are dealing with a disturbingly complex problem-a problem that demands a comprehensive solution.

It is unquestionably our drive toward specialization (stemming from a basic failure on the part of our whole educational system) which is primarily responsible for modern man's inability to provide directly for his own shelter needs. Despite this drift, I sincerely believe that the owner-built home can be an economic as well as esthetic success. It has been so for centuries, for thousands of families-if not millions-and continues to be so today. Furthermore, the process of building one's home can become one of the most meaningful and satisfying experiences in one's life-as indeed it should. Owing to the physical limitations of the owner-builder, and those impositions fostered by society in the form of restrictions and general mis-education, one can expect only to approach the completely self-tailored home. On one or more scores compromises are in order, but to the extent that the owner retains full control over his design and his work, he is successfully participating in creative building.

My limited experience in the building design and construction field in this country has taught me one very important lesson; satisfactory progress with the low-cash cost, owner-built home can come only after an entirely new approach to materials, structure, finished appearance and the occupants' basic pattern of living. I view our existing ego-inflated, overmaterialistic and downright absurd housing forms as gross impediments to the sort of rational and economic building that is actually possible and desirable. But to find intelligence in housing today one must go to the countries which, out of sheer necessity, are beginning to approach the housing problem at its roots.

In Asia, for instance, 150 million families live in overcrowded and unsanitary quarters. Some countries, like India, are attacking this situation with energy and imagination. A series of Aided Self-Help programs are included in the Indian government's three-year Community Development plan. At the International Exhibition on Low Cost Housing held at New Delhi a few years ago, a complete model village was on display. Over 30,000 people visited this village each day; it proved to be the most successful low cash-cost demonstration center in the world. None of the dwellings in this village cost over $1,000. Besides the wide variety of domestic buildings, the village contained a school, health clinic, co-op store, carpentry shop and smithy. The village was laid out with proper regard to water supply, drainage, lighting and street planning. This demonstration center also illustrated the wide variety of low cash-cost materials available; reeds, aluminum, gypsum, hessian, rammed earth, and concrete-employed in new and more imaginative ways.

The new structural ideas, uses of materials, and methods of design that result from an effort such as the New Delhi Exhibition mark a tremendous architectural advance-but the human advance behind the scenes is even greater. The best thinkers in their field have been on the job. Men like Kurt Billig, director of the Central Building Research Institute (Roorkee), A. L. Glen, (Pretoria), and G. F. Middleton, Commonwealth Experimental Building Station (North Ryde, New South Wales, Australia) could command the highest fees from those most able to pay. Instead, they contribute their vast store of building knowledge and imagination to the greatest housing needs of our age. Architect Joseph Allen Stein, head of the Dept. of Architecture at Bengal (India) Engineering College, summed up my sentiments in effect when he made the following statement at the New Delhi exhibition:

Centuries of privation, of social and economic inequality, have conditioned vast numbers of human beings to endure surroundings that can only be called sub-human. Today, architects, engineers and planners are called upon to show that a pleasant, healthful, human environment need no longer be the monopoly of a fortunate few.

It is a rarity of the first order when a dean of an architectural college takes it upon himself to build houses out of woven split bamboo between two layers of treated clay! These readily available materials were artfully used by Professor Stein in his creation of two demonstration low-cost homes. In his own words, the design

was worked out so that under proper conditions of community organization, such buildings can be built by village families with their contributed labor, without dependence on extra-village materials- on the basis of a program of guided self-help. The skill required for this type of construction is readily acquired; a two-months' apprenticeship is usually considered time for man to become a skilled bamboo worker.

If properly used, bamboo and clay construction can be expected to last as long as many manufactured materials that are considered to make permanent industrial housing. Standard materials for urban construction, such as corrugated iron sheets, poorly burnt, inferior bricks, or unseasoned wood can hardly be expected to last 25 years under average urban conditions. Yet even in the extremely hot humid climate of West Bengal and Assam, there are many clay and bamboo structures of 40 years of age. When replacement or repair is required due either to accident or deterioration of age, the materials are readily at hand, and the householder himself can do the work. The roof is of such a design that repairs can be made to any portion without affecting, or having to break up, the remaining part.

(The rural house) . . . is constructed of only three materials; it utilizes wood for the roof framing; the remainder of the construction is of earth (clay) and bamboo. In villages where wood is not readily and cheaply at hand, bamboo can be substituted. The sole purchase from outside the village is creosote, or other preservative materials; desirable to prolong the life of the structure.

Some of the world's "underprivileged" countries maintain a caliber of low-cost housing research which surpasses that of the far more wealthy countries such as our own. More significant research material is coming out of the South African Research Institute, for instance, than from all the HHFA, FHA, FPHA agencies combined. A recent housing development in South Africa (illustrated above) made use of such construction features as "no-fines" concrete (crushed stone and cement) for surface beds, and single thick brick internal walls-plastered on both sides. Detailed investigations were made on every item of expense that went into the experimental house.

In this hemisphere the most important low cost, owner-built housing research is being done at the Inter-American Housing and Planning Center (Bogota, Columbia). Two years ago this agency built a demonstration soil-cement house at a cash cost of $375. Designed for the cool climate prevalent on the Andean plains, the house has a living room, kitchen, two bedrooms, covered porch, storage room, shower, and laundry area, apart from an outside latrine. Roof members were constructed with eucalyptus tree limbs. Common clay tile was used for the roof, placed with a mud mixture on a frame of split bamboo. The floor was constructed of tamped earth, covered with a layer of weak cement and soil-cement floor tiles.

My personal approach to housing utilizes technical features similar to those of the low-cost housing research mentioned above. In following chapters on the subject, however, I introduce an evolutional frame of reference. The sort of house that I propose involves a process of growth and development for its realization-not only from the first conception of design and plan to the final nail that is driven, but also an internal growth and maturation on the part of the owner-builder. And the end-product is as different from the reactionary contractor-built, bank-sponsored, tract house as it is from the revolutionary architect-designed, owner-financed suburban home.

What distinguishes my proposed evolutionary form of owner-built home is its fitness for purpose and pleasantness in use. Volume I of my thesis, under the heading SITE AND CLIMATE, concerns the ways and means by which one can relate the house to regional and landscape conditions-heat and cold. Volume II includes chapters which evaluate the potential MATERIALS AND SKILLS that go into the owner-built home. Volume III deals with FORM AND FUNCTION-the actual room planning aspects of the owner-built home. Finally, Volume IV has to do with DESIGN AND STRUCTURE. In this series I discuss at length the various components of the house itself-from foundation to roof covering.

In my judgment, a positive philosophical outlook and way of life must necessarily precede the achievement of a quality owner-built home. This is to say that a truly satisfying home must develop from other and more subtle patterns. The mere technical problems of building a home are insignificant when compared to an understanding and interpretation of one's innermost feelings and thoughts concerning his shelter needs. But if these feelings and thoughts are not consistently related and released in daily activity, or if they become life-negative in orientation, then one might just as well discount the prospect of creating a satisfying home.

Thoreau said:

What of architectural beauty I now see, I know has gradually grown from within outward, out of the necessities and character of the indweller, who is the only builder- out of some unconscious truthfulness, and nobleness, without ever a thought for the appearance, and whatever additional beauty of this kind is destined to be produced will be preceded by a like unconscious beauty of life.

BUILDING SITE

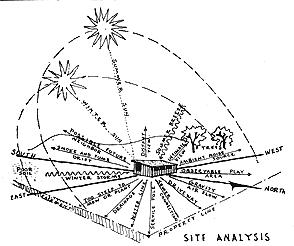

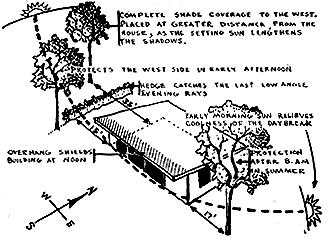

The above sketch illustrates some of the more important site conditions which can and should play a dominant role in influencing the design of the well-planned, owner-built home. Influences of site on building design are little understood and little appreciated aspects of conventional building construction. Nevertheless, they are aspects which affect every person who uses the building. The realized design, in turn, affects the site, and these two features condition one's life and plans for years to come.

It seems entirely logical to me that every individually designed home should have more than the usual degree of site planning. Besides being expressive of its owner's life, a home should be at one with its site and regional ethos. A man building his own home can afford to spend the time necessary to acquaint himself with the physionomic-climate site environment. The speculative or commercial builder usually fails to take enough time from his actual house-building program to know the character of the land upon which he is building. Results of this neglect are always unfortunate.

When the individual prospective home builder becomes acquainted with even a few of the specific site conditions found on his plot, he will come to appreciate the fact that sites tend to vary as much as people. No two sites are the same; no two regions are the same; no two climates are the same. Hence every building design problem must be solved individually. I should add, of course, that no two persons are the same, nor do they have the same needs. We are dealing with three independent, though inter-related, components; people, site and building. Both visually and actually, the building exists only in relationship to the site and surrounding landscape. And in the same manner, the site exists in relation to people-through the introduction of the house.

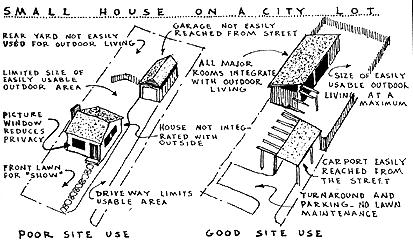

It is important to consider the house and site as one indivisible whole. The house-planning and site-planning process must go on together, with equal consideration to the design of every square foot of indoor-outdoor space. Lawns and workshops and gardens contain essences of their own; and it is as important to the total design concept that these be adequately expressed as it is that the essence of "living room" be expressed. It is something of a help to think of the house and site as a coordinating grouping of related indoor and outdoor rooms. In contemporary design work we are apt to concern ourselves with the psychophysiological requirements of interior space, and exclude a consideration for the equally strong need which people have for a satisfying relationship to the outdoors. The control or lack of control of climate can be as important a design feature as the determination of the refinement of interior surface materials. One's relationship to view or to plants can be an extremely significant design feature, as I will try to illustrate.

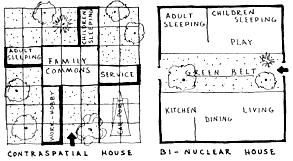

The so-called "Contraspatial" house grew out of thi's integrity-of-the-site concept. Another type, the "Bi-nuclear" house, has also been gaining popularity in recent years. But for every serious attempt to achieve integration of house to site, you will find a thousand houses peppering the landscape which clearly demonstrate the builder's total disregard for even the most basic consideration of sun, wind and view. In between these extremes you will find scores of half-baked efforts which try hard to achieve some semblance of site-relationship. I am more critical of these latter abortive efforts than of the former. The contractor-built tract home is at least an honest failure, since it doesn't even try for integration.

A few examples of the half-baked or "modern" efforts may suffice as forewarnings to the owner-builder in his approach to site planning.

The urge for a dramatic architectural effect usually impels the modern designer to place the structure on the most prominent position of the site. Or, for ease of construction and access, the house is located on the most level portion of the site, irrespective of associated, outdoor functions. Actually, it is the outdoor functions which require level gound; the house itself can be located on precipitous topography, often to great advantage. It is usually a mistake to build upon the most beautiful, most level section of the site. Once this area is covered with massive structure, its original charm is destroyed.

The "machine-for-living" approach to house-design and site-planning is about as false to man's true living needs as the art-for-art's sake approach is to his practical needs. In the former case, all important rooms in the house are oriented due south-irrespective of outlook or interior planning. The idea, of course, is to achieve maximum heat-gain in winter, and minimum heat-gain in summer. All the rooms end up with the same lighting conditions, as all the rooms have the same amount of south-oriented glass.

Glass is one material very much misused by modern designers. They respond to the bring-the-outdoors-in notion with floor-to-ceiling sheets of crystal. Paradoxically, the opposite effect is usually created; namely, claustrophobia, which results in the urge to break the glass and get out! Obviously, the glass restricts an easy ingress and egress, though it succeeds in suggesting such movement.

The "picture window" is, of course, the epitome of the mistaken bringing-the-outdoors-in notion, now held by ding-bat contractors everywhere. Picture windows are to homes what show-windows are to stores. They extend the market-place mentality with its display of things. In essence, the picture window provides a vicarious experience; more people can sit in their armchairs and look at, not live with, nature.

My final example of the ways in which modern dwellings fail in integrating house to site has to do with view. When one is fortunate enough to have a site with a dramatic outlook-especially to the south or east-the natural inclination is to orient all the major rooms toward that direction, and to use glass in as much of the view-wall as structurally feasible. A house so constructed speaks to me of arrogance and greedy self-importance. At best the end result is unpleasant and distracting,

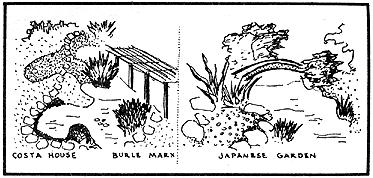

On the matter of view, we can learn much from Japanese builders. (Readers of this book will find frequent reference to Oriental architectural features. I have long felt that the traditional Eastern forms have more to offer the modern-day owner-builder than most of our up-to-date source materials.) A general practice among the Japanese is to place the house so that the same view is never seen from more than one vantage point-except in instances where the second view presents a contrasting element not seen by the first. In my own design work, I try to achieve a sequence of outlooks-from entry into the front yard and entry into the house, to a final view stepping onto the outdoor terrace. The owner-builder should investigate the prospects for varieties of outlook, and perhaps employ some of the many devices for enhancing it. One good idea is to develop a contrasting element between the long view (such as a distant mountain range) and short view, the garden-patio. Again, it is unpleasant to view something perpendicularly through glass. The Japanese stay clear of picture-like impressions by off-setting the center-of-view interest, and by creating hidden, around-the-corner vistas.

In his book, Japanese House and Garden, Dr. Jiro Harada gives the final word on view when he tells what Rikyu, a famed Japanese tea-master, did more than 360 years ago to give his garden deep spiritual significance:

When his new tea-room and garden were completed at Sakai he invited a few of his friends to a tea ceremony for the house warming. Knowing the greatness of Rikyu, the guests naturally expected to find some ingenious design for his garden which would make the best use of the sea, the house being on the slope of a hill. But when they arrived they were amazed to find that a number of large evergreen trees had been planted on the side of the garden, evidently to obstruct the view of the sea. They were at a loss to understand the meaning of this. Later when the time came for the guests to enter the tea-room, they proceeded one by one over the stepping-stones in the garden to the stone water-basin to rinse their mouths and wash their hands, a gesture of symbolic cleansings, physically and mentally, before entering the tea-room. Then it was found that when a guest stooped to scoop out a dipperful of water from the water-basin, only in that humble posture was he suddenly able to get a glimpse of the shimmering sea in the distance by way of an opening through the trees, thus making him realize the relationship between the dipperful of water in his hand and the great ocean beyond, and also enabling him to recognize his own position in the universe; he was thus brought into a correct relationship with the infinite.

My chart No. 1 cannot indicate what is perhaps one of the most important aspects of site planning; the site's physiognomy; that is, the essense, spirit, or original individuality of the site. If the owner-builder is fully aware of his particular site-as it relates to the ethos of the regional landscape and character of the existing neighborhood-he will not go far wrong in his site-planning practices. Much can be said about the human feeling towards the setting, especially in regards to one's immediate plot of ground-the microcosmos and micro-climate of a half-acre lot, say. I have certainly seen the effect that care and loving attention can have on a setting. Really high-quality site developments result where seemingly the only investment is imagination tempered by a full realization of the profound assets which lie within each site. Ambient forces were allowed to exert their full energy, unhampered-but on the contrary, developed-by personal re-directions.

The best approach to site development lies somewhere between the "masterful" and "subservient" levels. One should neither wreck the site nor fail to develop its character. Richard Neutra speaks of the consequences of disregard for the site's individuality:

. . . try to understand the character and peculiarities of your site. Heighten and intensify what it may offer, never work against its inner grain and fiber. You will pay dearly for any such offense, though you may never clearly note what wasting leak your happiness has sprung.

Once this "feeling-for-the-site" apsect has been achieved, one should begin the house plan by first drawing a site plan. (A house plan can only be drawn on a site plan; both site and building must be regarded in the same light.) Three general areas of space are outlined; the public area, the private area, and the service area. Under each heading, list all the space requirements proper to it; a patio-garden living room, a game-play area for children; an outdoor work area (crafts, hobby projects, auto repair); outdoor storage facilities for garden tools, firewood, lumber, compost; a trash-area; plant structures (lathhouse, greenhouse, garden work-center); a vegetable garden, fountain or swimming pool, perhaps some animals . . .

As your desires and needs are listed, the space allotments for their satisfaction plotted on the site map, the plan will blossom and begin to take form. Like a successful jig-saw puzzle, each component will fall into its obvious, unmistakable position. You will know that this particular function must take place at this particular place on the plan, and that this amount of space must be allocated for this other particular need. Soon the whole scheme will become immediately perceivable. It will be right, and you will be sure of its rightness. And you will know when the time has arrived for the first stage of plant arrangement and building design.

BIBLIOGRAPHY (books listed in order of importance)

Mystery and Realities of the Site: Richard Neutra, 1951

Looking Through the Picture Window: Bernard Rudofsky

The House: Robert Woods Kennedy

Japanese House and Garden: Jiro Harada

Japanese House: Yoshida

Natural Principles of Land Use: E. H. Graham

Chinese Houses and Gardens: Henry Inn

Land and Landscape: B. Colvin

PLANTING DESIGN

A new approach to planting design is now in its formative stages. Advocates of this new design-concept maintain that the interior space should be harmoniously extended and connected with the space outside. It is demonstrated that the very same principles of building-design apply to the outside planting-design. Every plant, no matter what form it may take is a construction in space and an enclosure in space.

As enclosures of space, plant forms expand from the walls, floors and ceilings of rooms to the hedge-wall, lawn-floor and tree-ceiling outdoors. Again, outdoor shelter-forms, such as arbors, pergolas and pavilions, find shelter-counterparts within the house. And as constructions of space, the sculptural effects of rocks, flowers, garden pools, and specimen plants can be likened to furnishings and utensils of the building interior.

This integral concept of building and planting was actually practiced by the 18th century Chinese. Called Feng shui , the basic principle was derived from the teachings of Lao Tze, the 6th century Chinese philosopher who taught a return to nature. Nature and man were harmonized in the Chinese garden. The garden was symbolic of nature, while the house was reserved for man. That is, where the house served man's practical and serious needs, the garden was a place for the playful, romantic and carefree side of man. In the house man is in the society of his fellow beings, but in a garden he is in the society of natural forms.

It has been said that inside the house the Chinese gentleman is a Confucian-adhering strictly to the conventions and moral codes set down by Confucius. But in the garden he is a Taoist-following the primitivistic, libertarian precepts of Lao Tze. It is interesting to note that while the Chinese house is orderly and formal in style, thus limiting the spirit, the garden forms are irregular and sinuous, and so give the spirit release. According to Wing-Tait Chan, the Chinese garden is a "place where man laughs, sings, picks flowers, chases butterflies and pets birds, makes love with maidens, and plays with children. Here he spontaneously reveals his nature, the base as well as the noble. Here also he buries his sorrows and difficulties and cherishes his ideals and hopes. It is in the garden that men discover themselves. Indeed one discovers not only his real self but also his ideal self-he returns to his youth. Inevitably the garden is made the scene of man's merriment, escapades, romantic abandonment, spiritual awakening or the perfection of his finer self."

In Western gardens we seek more of the comforts or conveniences which people have come to consider essential to their well being. Another factor is garden beauty; we arouse interest through variety of planting, excitement through planting sequence, stimulation through planting color. In any case, it is the activity of people which determines the form and character of garden planting.

Modern landscape designers employ hundreds of devices in a so-called "bag of tricks" to satisfy modern-day beauty-and-comfort requirements. For instance, a shrub can be planted to create a dozen different effects, depending upon its placement and relation to human scale; if the plant is above eye level it can function as protective enclosur. if it is kept to chest-height, the effect is more of spatial division; if the planting is waist-high, it functions as a traffic control element; knee-height gives a directional aspect to the planting. It is the human scale-in the event, the person's height-which relates and measures the garden elements, fences and trees as well as shrubs. And the human line vision determines whether these landscape elements will provide privacy, separation or direction.

Eckbo is surely the most noted representative of the modern landscape movement. His book, Landscape and Living, is a clear statement and concise presentation of modern landscape objectives and practice: Eckbo-gardens are beautiful designs of plant-structure relationships, and contain all the amenities so eagerly sought by up-to-date home owners. In all of his gardens you will find the plant and structural elements well selected. Also, the groupings-forms and masses of plant elements-are well arranged. Furthermore, the whole scheme is very practical from maintenance point of view.

But minimum maintenance with maximum charm and "out-door living" is not, in my book of planting-design, quite enough. Modern landscape designers miss the boat entirely as far as designing for spiritual "uplift" is concerned. Where can one find a garden (this side of the Orient) which gives man essential revitalizing contact with the plan growth and fecundity of the earth? The Chinese captured this essence in their garden plans, and themselves gained strength and inspiration in the garden space. And I find very few modern garden-designers with any concept of Spieltrieb- the playful instincts expressed in plant forms and garden structure. The idea that a garden can be a home of gaiety, of imagination, of fantasy-as well as a place for meditation and repose-seems alien to modern thought on the subject.

I have great respect for one architect, however, who has successfully expressed the Spieltrieb concept in a garden plan for a modern Italian muralist. Bernard Rodofsky speaks of his design in these terms:

A free-standing wall, plain and simple, with no special task assigned, today is unheard of. In a garden, such a wall assumes the character of sculpture. Moreover, if it is of the utmost precision and of a brilliant whiteness, it clashes-as it should-with the natural forms of the vegetation, and engenders a gratuitous and continuously changing spectacle of shadows and reflections. And aside from serving as the protection screen for the surrounding plants, the wall creates a sense of order. Three abstract murals compete with the umbrageous phantasmagories.

An old apple tree pierces one of the walls, lending it (methinks) a peculiar monumental quality. The pergola is reduced to almost linear design, and does not intend to more than assist and coordinate. A wisteria has taken possession of it in the space of a few months; bamboo shades are hung from it in summer. The wiry appearance of the poles is accentuated by bright colors. The solarium is an ample room with immaculately white walls, a floor of red brick set in sand and a diminutive lawn. Wall openings were omitted to avoid drafts; the solarium is accessible by stairs only.

Another exceptional landscape architect, Roberto Butte Marx, expresses the Spieltrieb element in bold and positive terms. His designs are curving freeform reactions against symmetry and rectangularity. One of the more interesting things about Burle Marx's gardens is his attractive use of native plants-plants considered to be mere weeds among other gardeners. He searches his native (Brazil) jungles for indigenous plants and combines their placement with a skillful use of stone mosaic and waterpools.

The central purpose of this chapter is to offer the home-builder a working outline for landscaping his new home. For many years I have been collecting data which can be used as a basis for good planting-design procedure. My approach has not been along "modernistic" landscaping lines-nor have I tried to analyze the even more subjective and symbolic forms of traditional Chinese and Japanese gardens. Rather, I have attempted to organize a planting-design procedure which is based entirely on the ecology of natural vegetation; the relationship, that is, between plants, climate and soil as well as between one type of plant and another. My theory is that, once this harmony is created, the garden-beauty and comfort-producing factors for man's garden enjoyment will be automatically forthcoming. Then whatever else happens in the garden landscape-in terms of the Spieltrieb element, for instance-will be entirely up to the home-owner, his personality and likes and dislikes. I would hope that this latter aspect, too, will be automatically forthcoming-once the landscape retains natural balance.

Rudolf Geiger is one of the earliest climatologists to indicate what direction this "new" planting-design might take. His excellent study on the microclimate also indicates procedure and method for achieving this new garden form. He found, for instance, that a mixed forest growth of spruce, poplar and oak effectively cuts off from the ground 70% of the sun's heat. Forests are cooler than cleared land in summer, and warmer than cleared land in winter. Nature keeps the ground covered with vegetation. With this heat-absorbing surface, heat previously held by the soil is transferred to the top layer of plant foliage. This layer-to-layer transfer and exchange from a dead to a living thermal-absorbing surface provides definite summer-cooling and winter-warming effects. An evergreen windbreak is also effective in reducing heat loss from buildings-by keeping the cold winds out of contact with building surfaces. Drifting snow is discouraged by well-planned evergreen hedges.

The more significant function of natural vegetation is demonstrated in summer time. No doubt everyone is aware of the important summer-shading effect of trees (although the barren tract-developments sometimes leave one to wonder how this most basic of all climate-control features could be missed by so many builders). But even a good understanding of how the deciduous tree provides generous shade at exactly the appropriate summer season-and then loses its leaves toward autumn so the sun can easily penetrate through the leafless branches during winter-is really not enough information to assist the amateur home-builder in his selection and placement of trees. Climate-control experts employ a Heliodon-an accurate, simulated sun machine-to determine the exact, most desirable position of vegetation around buildings. The Olgyay brothers, professors of architecture at Princeton University, have published more vital information on this subject than the rest of the climate-control research agencies combined.

The shape and character of the shade tree will determine the extent and shape of its shadow. The variety chosen should therefore depend upon the shape of the area to be shaded. For instance, the maple and ash produce circular shadows, with an ascending branch pattern in winter. Honey locust and tulip trees have oblong shapes. The white oak is wide and horizontally oblong, with an open-branched structure. The Lombardy poplar is columnar and the American elm is vase-shaped in appearance. Other trees especially recommended for shade purposes are; weeping willow, Russian olive, flowering dogwood, sweet gum, American beech, maple, white birch, and Siberian crab apple.

The effect that plants have on the heat and moisture content of the soil and air is little recognized among modern landscape gardeners. The usual mistake made is in planting shrubs too close to the house. This may make an attractive "design"; but the density of the shrubs has a tendency to prevent breezes from penetrating, which in turn reduces evaporative cooling and causes high humidity and high temperatures to persist within the foliage of this type of vegetation. Trees and grass near the house, on the other hand, allow the heavier, cool air to flow inside (providing the window openings are adequately designed, a subject reserved for the following chapter). Leaves and grass naturally absorb solar radiation and the resulting evaporation cools the surrounding air. Mowed turf is an especially good climate-control planting, as in shading the soil it prevents heat absorption by it, thereby eliminating intensive re-radiation.

Dr. Robert Deering, University of California professor of agriculture, reports that when trees are planted near the south glass wall of a building several desirable effects occur. The north side of the tree, facing the south wall of the building, is the "chilling" side of the tree, which results in a cooling effect in the house. Annoying glare can also be substantially reduced by so orienting the tree placement. Air-borne sounds can be effectively reduced by densely planted trees and shrubs. The viscous surfaces of leaves catch dust, thereby functioning as excellent air-filters.

In Europe, vines are used for controlling evaporation and providing shade much more than in this country. Vines are especially desirable when grown against or near the west wall of a house. Recommended are; clematis, bittersweet, frost grape, parthenocissus, hydrangea petiolaris, wisteria, silver lace vine, Chinese fleece vine, Dutchman's pipe, forsythia, ipomoea.

Perhaps the latest, least understood concept of landscape design has to do with the selection and arrangement of plant material on the basis of color-fragrance relationships. Florence Robinson's book on this subject proved to be of some assistance. Eckbo made many significant comments on this aspect of planting design. In areas of high humidity, the darker, heavier and glossier greens are prominent. However, this tends to accentuate the oppressive, discomforting climate of high-humidity regions. Therefore it is better, from a climate-control point of view, to encourage the lighter, clearer greens. Thinner plant forms should be grown in cool areas, and where the atmosphere is dull and dark there is advantage in going to silver and gold variegations.

In hot-dry zones of low humidity, the natural vegetation is dull and fuzzy. The landscape quality is thinner; and grays, gay-greens and brown-greens predominate. But, in this type of climatic region, it is best to promote the growth of darker, brighter, glossier or clearer greens. The larger and richer foilage feels cool and moist-a most desirable feature for use in arid regions.

An enlightened approach toward planting-design demands, first of all, a thorough understanding of one's region and site. This basic understanding, which includes information about weather, soil and native plant life, must necessarily precede an intelligent treatment of climate-control procedures. For, after all, the primary objective in planting-design relates to the creation of a satisfying environment-climate-wise as well as in esthetic content.

A whole chapter on this subject of climate-control can therefore be profitably included in this book. We must dig deep through the mire of information and misinformation and arrive at some basic principles. Those principles will ultimately lead us to rational planning of our home in its natural environment.

BIBLIOGRAPHY (books listed in order of importance)

Landscape for Living: Garnett Eckbo

Solar Control and Shading Devices: A. & V. Olgyay

Cooling Effect of Trees and Shrubs: U. of California at Davis, Dr. Robert Deering

Plant Communities: H. J. Costing

L'Elenento Verde and L'abitazion: Quaderni d' Domus, Figini Luig

Climate Near the Ground: Rudolf Geiger

Planting Design: Palette of Plants: Florence Robinson

Gardens in the Modern Landscape: Christopher Tunnard

Modern Gardens: Peter Shepheard

Plant Ecology: Clements

Landscape Magazine: Box 2149, Santa Fe, N.M.

The Recovery of Culture: Henry Stevens

The New Exploration: Benton Mackaye

COMPOST PRIVY

"Modern architecture is a revolt against styles and is based on the intimate awareness of functional requirements in the broadest sense of the word "function". Unfortunately, the revolt preceded the research needed to start establishing these functions."

Architects Journal, 1965

In this multi-volumed and progressively-written book I have attempted to present the results of my research precisely along the lines of the functional revolt-as applied to the low-cost or owner-built home. In the course of my thinking and writing, I have been guided somewhat by readers' comments and questions on previous chapters. These have constituted a kind of feed-back on my researches. What were the readers' particular problem areas? Such considerations should assist in the formation of new chapters or supplements-even new volumes or books.

The present chapter is a definite response to readers' comments. More readers picked up an offhand mention of the squat-toilet (p. 38) than any other item in Volume III. So the squat-toilet idea will be discussed here. And it will be discussed in its proper context as a feature of the large problem of bathroom waste disposal. A proper toilet suggests a proper disposal system and this further suggests a proper structure to accommodate the necessary facilities.

And by "proper" I refer, as usual, to Ralph Borsodi's criteria: Is it healthful? Is it economical? Is it pleasing to behold? One need not be reminded that modern bathroom systems are ugly, expensive and unhealthful. If you wish to know how much your conventional bathroom plumbing and drainage system costs, count the number of fixtures in the house, including lavatories, water closets, bathtub, water heater. This total multiplied by $400 gives a close estimate of plumbing costs. Add to this the room area multiplied by $10 and you have a surprising total of about $2500 for an average-size bathroom and drainage facility.

Finally, the "healthful" aspects must be considered. It can be factually stated that the conventional water toilet is not healthful. The high sitting position is artificial and unhygienic. Nor is it healthful to pollute bodies of water with water-borne sewage. Each year 4.5 million tons of sewage sludge is dumped into the oceans from North America. This represents 4.5 million tons of nitrite contaminant and it also represents 4.5 million tons of potentially valuable fertilizer not returned to the land. The experts are in unanimous agreement on the subject of toilet height (as quoted from Kira's book):

The ideal posture for defecation is the squatting position, with the thighs flexed upon the abdomen. In this way the capacity of the abdominal cavity is greatly diminished and intra-abdominal pressure increased, thus encouraging the expulsion of the fecal mass. The modern toilet seat in many instances is too high even for some adults. The practice of having young children use adult toilet seats is to be deplored. Beckus, Gastro-Enterology, p . 511.

Man's natural attitude during defecation is a squatting one, such as may be observed amongst field workers or natives. Fashion, in the guise of the ordinary water closet, forbids the emptying of the lower bowel in the way Nature intended . . . It is no overstatement to say that the adoption of the squatting attitude would in itself help in no small measure to remedy the greatest physical vice of the white race, the constipation that has become a contentment. Hornibrook, The Culture of the Abdomen, p . 75.

It should be mentioned in this connection that a very common cause for unsatisfactory results . . . is improper height of the toilet seat. It is usually too high. An ideal seat would place the body in the position naturally assumed by man in primitive conditions. The seat should be low enough to bring the knees above the seat level. Williams, Personal Hygiene Applied, p. 374.

The high toilet seat may prevent complete evacuation. The natural position for defecation, assumed by primitive races, is the squatting position . . . When the thighs are pressed against the abdominal muscles in this position; the pressure within the abdomen is greatly increased, so that the rectum is more completely emptied. Our toilets are not constructed according to physiological requirements. Aaron, Our Common Ailment , p.66.

The Thailand government has had a long-established program of improving rural latrines at Chiengnai. Perhaps the most recent achievement in this area has been the development of a water-seal squat-type (squatting plate) toilet bowl that any farmer can build for less than a dollar's worth of material. The Thailand Ministry of Health sells a 2-component cast aluminum master mold from which countless numbers of units can be built. I secured a couple of these Chiengnai molds for our owes experimentation-and to loan out to people interested in building their own toilet bowls.

The finished toilet bowl is quite satisfactory. It takes about one quart of water to flush the unit-as opposed to 4 gallons for the conventional water closets. The bowl can be maintained clean and sanitary without difficulty. And most important of all, the use of this bowl necessitates a natural evacuation posture.

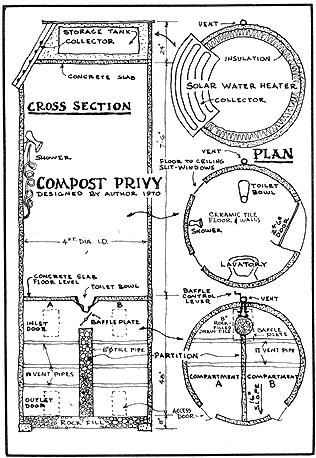

The use of a squatting plate suggests a re-evaluation and redesign of the complete bathroom facility. The room I propose is in effect a four-foot diameter shower stall. A single flexible water inlet-of the type commonly used in Denmark-supplies showering, lavatory washing and bowl flushing. A single drain disposes of all wash and flushing water through the bowl trap. (Ideally, a solar water heater and storage facility directly overhead supplies consistent warm water needs.) Directly below the squatting plate an excreta-disposal compartment is provided.

There are two basic methods of excreta disposal: The compost privy and the septic tank. The first process is aerobic and requires oxygen in its fermentation process of decomposition. The second is anaerobic and consists of a putrefactive breakdown-in places where oxygen does not have access. We must choose between fermentation and putrefaction in our attempt (1) to reclaim the nutrient and fertilizer value of waste, and (2) to dispose of excreta waste in a sanitary manner.

World Health Organization publications present a compelling argument against handling excreta in an anaerobic (sewage and septic tank) manner. As a result of not having oxygen in a putrifactive action, no heat build-up occurs and therefore certain pathogens and parasites are not fully destroyed. It has been found that contaminated material in liquid suspension (anaerobic digestion) can remain viable for as long as six months. For one thing, there are far more species of bacteria involved in aerobic decomposition than in anaerobic putrification.

Other problems are associated with the disposal of water-borne waste. Sewage necessarily containing large quantities of water (necessary for the transport of the excreta) is difficult to treat. Water does have a certain ability for self-purification. But this requires oxidation and usually the volume of water is too small in proportion to sewage to supply the required quantity of oxygen. Consequently the receiving water becomes foul and normal fauna (especially fish which require oxygen to live) are destroyed. The receiving water also becomes contaminated with pathogenic bacteria, protozoa, and with the eggs and larvae of harmful helminths (liver flukes).

Our society not only legalizes pollutive unsanitary disposal methods, it also outlaws an improved nutrition-an essential factor in prevention of disease-which is obtained when excreta wastes are returned to agricultural lands as plant nutrients.

The only really practical way to reclaim these wastes is through aerobic composting. Pathogenic bacteria and worm eggs can survive no longer than 30 minutes to 1 hour in a compost situation. Compost temperatures rise to 160 degrees F. High temperatures, however, are only partly responsible for this bacteria destruction; competing bacterial flora and predatory protozoa contribute as well. Aerobic composting is achieved by a wide succession of bacterial and fungal populations-each suited to its own environment and its own relative duration: The activities of one group compliment the other.

Humus is the end-product of properly composted organic materials. Humus contributes to increased nitrogen-fixation in the soil from nitrogen in the air. Also, as the gradual decomposition of insoluble organic matter takes place, nitrogen is liberated (as ammonia) and then oxidized to nitrates. Plants can utilize this nitrogen only in the form of nitrates. So when raw (not composted) wastes are spread on the land-as is commonly done in the Orient-nitrogen evaporates into the air instead of being used by plants.

The primary key to good compost-building is to establish correct proportioning and blending of the raw materials. In essence the problem is one of determining carbon and nitrogen ratios (C/N), along with the correct amount of moisture and aeration. Cellulose organic matter like straw or sawdust is rich in carbon, and excreta are rich in nitrogen. It has been found desirable to keep the C/N ratio above 30 to 1 when excreta is used; excreta should equal 10% to 25% of the total weight. Urine contains considerable larger amounts of nitrogen than do feces. Raw garbage has a C/N ratio of 25 to 1; sawdust, 511 to 1; farmyard manure; 14 to 1.

Aeration helps maintain the required high temperatures in an aerobic composting condition. Turning the compost pile at frequent intervals has been a traditional method of achieving aeration. Yet, turning adversely effects nitrogen conservation. Ammonia readily escapes to the atmosphere when the material is disturbed and exposed.

As one becomes more familiar with the whole process of aerobic composting, the design of an appropriate facility falls into place. The facility design can be likened to that of a furnace: Material (fuel) is placed in a combustion chamber; a vent stack (chimney) is provided to carry off gases that are produced from the decomposition (methane, carbon-dioxide, ammonia); and, finally, a storage compartment must be supplied for the end product (humus, or ash, in the case of a furnace).

The size of the facility depends, of course, upon the number of people using it. About 2 pounds of excreta per person per day, or 1 1/2 cubic feet per person per year, is used as a design figure.

If the initial C/N ratio is 30 to 1, it takes about 10 days composting time; a 78 to 1 ratio takes 20 days. Using the 1 to 5 volume ratio of excreta to refuse, and figuring that a family of five will produce about 1 cubic yard of partly digested excreta in four years, a compartment size of 1 cubic yard would fill in about 9 months. It must be remembered, however, that decomposition into gases and soluble materials reduces volume and mass as much as 80%.

The Indian Council of Agricultural Research at Bangalore developed extensive composting programs based on the compost privy principle.

They built an experimental "double vault" latrine. During the time that one compartment was being used, compost material in the adjacent compartment was ripening. A period of 6 months lapsed between clean-outs, This two-compartment system appears to be superior to others. However by incorporating a simple damper mechanism, only one squatting plate need be provided.

Rikard Lindstrom of Tyreso, Sweden, has patented a simple aerobic composting chamber. Its salient feature consists of a sloping (16-degree) bottom to the tank, which provides for a continual movement of the decomposed refuse to a storage chamber as additional wastes are added to the other compartment. The chamber bottom should contain a thick lays (12-inches) of straw or sawdust so that urine will be absorbed and reclaimed. This porous layer of cellulose also provides aeration to the central section of the pile. Lindstrom used a system of inverted U-shaped conduits and ventilation holes to provide adequate aeration. Air circulation is also accelerated through solar-heated flue conversion.

In Japan, where excreta is traditionally used as a fertilizer, powdered soybean is often added. Enzymes in the soybean speed up the breakdown of organic solids. Kazuyoshi Yamaji of Tokyo holds a U.S. patent on a "powdered deodorizer of the acceleration of ripening of organic fertilization fertilizers." A dried and powdered cereal containing a large quantity of enzyme is first mixed with rice-bran, barley-bran, or wheat-bran. Water is added and it is heaped for fermentation. It is then dried and powdered and mixed with tricalcium phosphate and the powder of germinated seeds of cereal such as barley, wheat, bean, etc. which contains a large quantity of enzyme. Only a small quantity of the finished product need be sprinkled on the excreta.

Bio-Dynamic gardeners use a special preparation-inocula-in making compost humus. The formula is based on the researches of the late Dr. Rudolf Steiner. One of these exotic preparations (502) is made from yarrow blossoms, fermented together with deer bladders over a period of 6 months in earth during the winter.

Using enzymes, hormones, or biocatalysts in the decomposition of organic material and for nitrogen fixation may prove to be an interesting sideline, but none of these inocula are really necessary to a properly balanced compost environment. Organic material contains all the growth factors and vitamins necessary for normal development. These growth factors are produced by micro-organisms in sufficient quantities in a mixed microbial population to meet normal growth requirements.

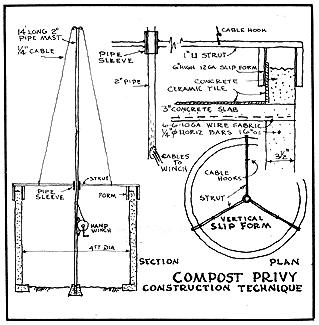

From the point of view of cost, health, and good design, I recommend the cylinder-shaped structure. The 4-foot diameter structure contains, in its series of levels: Effluent drainage pit, compost chamber, bathroom facility, solar water heater. A very simple slip-form jig can be employed to build the solid concrete walls. The complete unit is available from me for loan to interested people. Floor and roof are cast-in-place concrete. Ideally the unit would be built on a hillside to provide best access to the compost compartment. It can be built as a detached structure or connected to hall, breezeway or directly to sleeping unit. The accompanying drawings and photos best illustrate the structure and techniques of construction.

A widespread use of the compost privy is not to be expected. There are many social, legal, and technical difficulties associated with adopting this new functional mode of handling human excreta. For clarification on specific aspects, ask your friendly Building Inspector. In my judgement the long term personal rewards and benefits to the environment warrant whatever manner of subterfuge deemed necessary to build the compost privy. No County Building Department should have the power to prevent my squatting to relieve myself, nor should it prevent compost activities limited to my own garden.

BIBLIOGRAPHY (Books listed in order of importance)

An Agricultural Testament; Albert Howard

Excreta Disposal; World Health Organization

Composting; World Health Organization

The Bathroom; Alexander Kira

Fertility From Town Wastes; Wylie

MORE KEN KERN (THIS TIME "OWNER BUILT HOMESTEAD") COMING IN MOTHER NO. 7.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|